My Bank Recommended a Product, and I Was Skeptical

I was chatting with my wealth management advisor at the bank about investments when she mentioned "structured notes." It wasn't the first time I'd heard the term; I'd glanced at it elsewhere before, but it always seemed like a dense fog of financial jargon. Terms like "stock-linked," "150% upside participation," "capped return," "buffer zone"—it sounded like the finance world's version of a trendy gym membership package: stylishly packaged, sophisticated-sounding, but always leaving me wondering if there was something hidden inside I didn't understand.

I have a good relationship with my advisor; she wasn't pushing a sale but honestly introducing products that clients were currently interested in. She said something that stuck with me: "Many clients right now aren't actually looking to make huge profits. They hope to earn a bit more when the market presents opportunities and not lose too much when it goes down. These types of products are designed for that exact mindset."

This reasoning made sense. After all, the market has been quite volatile these past few years. Fast rises in the stock market make you envious, while sharp drops are nerve-wracking. Most people aren't chasing maximum alpha; they just want psychological security and a strategic safety net. But for some reason, a voice in my head still whispered: This looks too clever. Could it be too clever?

So, I made a decision. I'm not a professional investor, nor do I understand financial engineering. But I wanted to know what this structured note really was. What's the principle behind it? Why does it have this specific payoff structure? Could I achieve a similar goal using simpler, more transparent methods?

This wasn't about questioning the bank's motives. I fully trusted they were offering a product suitable for a certain type of client. My curiosity was about the structure itself: Was this product as ingenious as described? Or were there hidden trade-offs not explicitly stated in the brochure?

I decided not to burden my advisor with these questions, as it went beyond her job scope. I chose another path: I threw the term sheet at an AI.

The AI Unpacked the Note, Revealing Its True Form

My prompt was incredibly simple, perhaps even naive:

"Can you help me analyze this structured note? What does it mean? Are there any pitfalls?"

This turned out to be a crucial realization later: When you pose a professional question to an AI, it doesn't recite textbook definitions. It starts dismantling the problem directly. If you're willing to ask, it's willing to answer, step by step.

The AI's first response went something like this:

The core logic of this note is packaging a short-term bank bond (say, 14 months) with a set of options linked to a specific stock. It uses your principal to buy a bank bond and then uses the interest to purchase option contracts. For example, if META stock goes up in the future but doesn't exceed 35%, you get 1.5 times the upside return. If it exceeds 35%, you only get 35%. However, if the stock falls, you won't lose money as long as the drop doesn't exceed 15%; if it falls further, you start losing the excess amount.

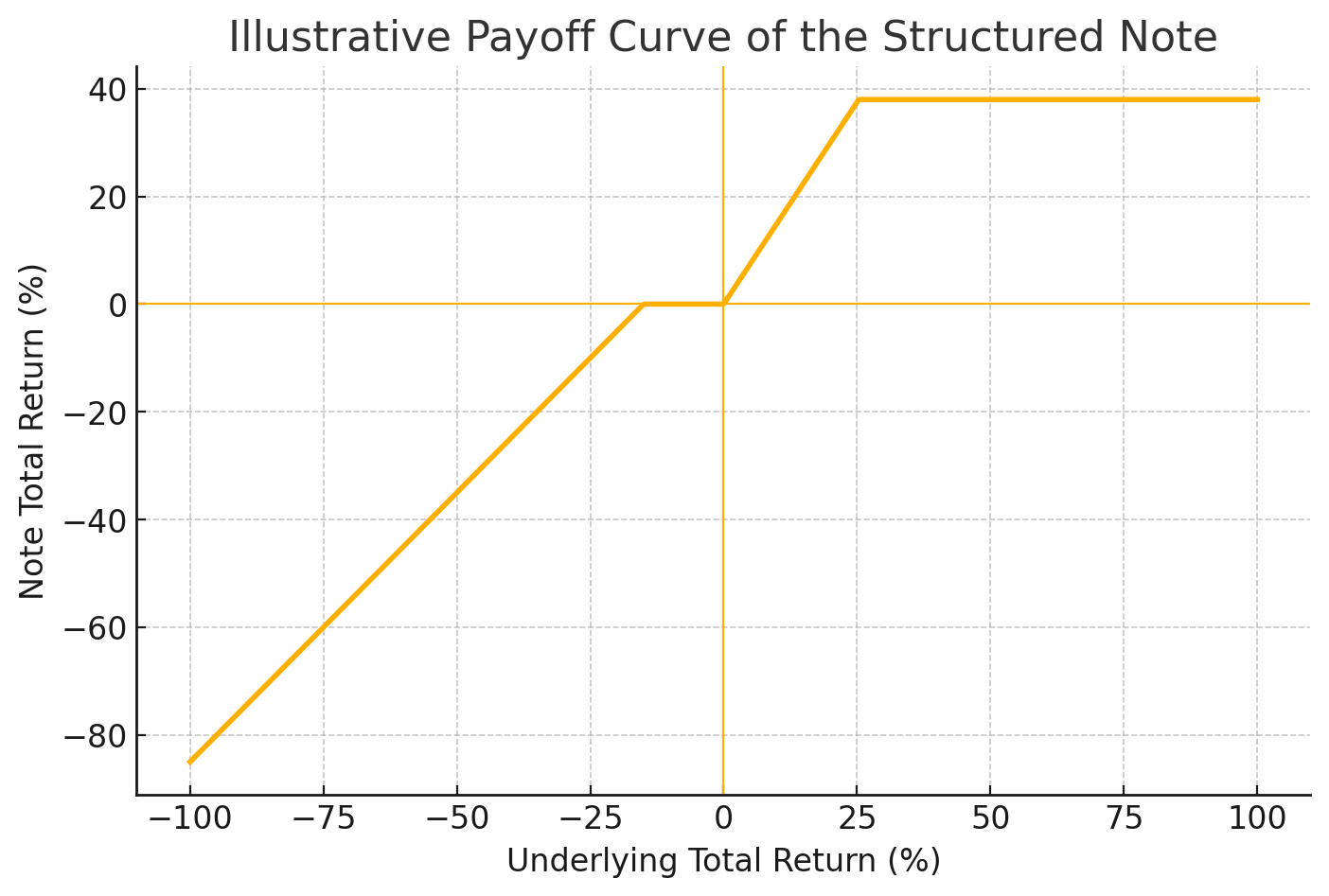

The AI even generated a chart showing the note's payoff curve under different market conditions.

Suddenly, it clicked. The note essentially trimmed the tails off the potentially infinite upside and downside of the market, leaving a comfortable middle ground. This safe zone is called the buffer, and the ceiling above is the cap. It seemed like guardrails were added, but they also limited the potential profit.

As a DIY enthusiast, I couldn't resist asking: "Could I create such a structure myself using options? Like buying a call, selling a higher-strike call, and adding some protective puts—wouldn't that be similar?"

The AI responded calmly:

Theoretically, yes. You could buy an at-the-money (ATM) call option and sell a call with a strike price 1.25 times higher, forming a 'bull call spread.' You could then add a put spread for downside protection to mimic the buffer. However, you need to be aware of several points: These options might have poor liquidity and wide bid-ask spreads in the market, you'd need to post margin, and these structures are often only cost-effective and optimally executed at an institutional level.

After reading the AI's explanation, my feeling was: Isn't this just selling information asymmetry? I could create a similar combination myself, yet the bank packages it as a note for end-users, profiting from the structure's opacity. Isn't this the standard financial industry playbook—translating option jargon into customer-friendly terms like principal protection, linkage, buffer, annualized return?

As I thought this, I subconsciously labeled the note: Clever arbitrage built on the backs of those unwilling to think. I believed I had seen through the logic of such products. I also thought that with a little AI and options knowledge, I was already upstream of the structure.

But a later discussion quickly made me realize: I understood the structure, not the system; I dismantled the logic, not the motivation. What truly opened my eyes to a deeper level of understanding was a conversation with a friend.

I Thought I Understood, But I Had Just Scratched the Surface

The AI had clearly broken down the structured note's composition: a bond, a bunch of options, capped upside, buffered downside, all wrapped in a credit shell. After seeing the payoff chart, I felt for the first time that I truly understood a financial product. But this sense of understanding was soon interrupted by a discussion with a friend.

I shared the payoff chart in a few group chats, adding comments like: "The structure is actually simple, just a bull call spread + buffer put. These notes are ultimately just packaged derivative portfolios; the bank profits from the lack of transparency."

But a friend's remark later hit me. He said that banks design structured notes not necessarily to give you the optimal investment portfolio, but to handle the risks you're least willing to manage yourself. You don't want to constantly watch the market, worry about margin calls, calculate implied volatility and tax implications, or access cheap over-the-counter (OTC) options for hedging. These are precisely the things banks excel at, often reducing costs through scale. So, what they're selling isn't cleverness, but peace of mind.

I paused. The payoff curve the AI drew was still vivid in my mind, like a logical blueprint. But suddenly, I realized I had approached these notes purely from a structural perspective: What does it look like? Can I build it myself? Is it worth buying? My evaluation framework was based on strategic cost-effectiveness, like a DIY enthusiast seeing a pre-made meal kit and thinking: Isn't this just assembling ingredients? I could replicate this at home for less, why pay extra?

I had understood the blueprint but missed the other side of the user manual—who this product is for, what problem it aims to solve for them, and under which psychological conditions it truly works. It dawned on me then: structured notes aren't strategy products; they are productized psychological engineering.

This reminded me of an observation discussed in our group: You can imagine the entire financial product market as a massive strategy translation chain:

- Proprietary trading desks discover a profitable structure or market mispricing and quickly capture most of the alpha using infrastructure and algorithms.

- Hedge funds stabilize and parameterize these structures, turning them into replicable, risk-managed mid-level models.

- Mutual funds package them into products, creating fundraising channels.

- Brokerages further process these products into regular investment plans or package them around industry themes.

- Banks, finally, take all this and refine it into a narrative that can be explained simply, using terms like buffer, cap, and participation rate, making it palatable to customers.

No one is deceiving anyone; it's a process where strategic complexity is progressively translated into language that human psychology can grasp. Each layer answers the question: How can this be made accessible to more people?

You think they're doing strategy, but they're actually doing translation. You think structured notes are cleverly priced, but their core advantage lies in clear structure, encapsulated risk, and simple delivery. Whether you can replicate a similar options structure yourself is, frankly, beside the point.

It's like beef stew. You can buy the meat, blanch it, simmer the broth, season it, and slowly cook it yourself—but many people prefer to pay for a ready-made meal that tastes decent, heats up instantly, and is foolproof. The bank isn't selling the secret recipe for the stew; it's selling saved time, risk isolation, and reduced cognitive load.

So, you can certainly choose to cook yourself. But when evaluating a ready-made meal, you can't just ask, "Could I make this dish too?" You have to ask, "Are there people willing to eat this way?"

And structured notes are for those people—those who don't have time to cook, don't want to deal with the kitchen, and just want each meal to be decent and uneventful.

I Tried Building a Note Myself and Found It Wasn't So Simple

After our discussion, I couldn't resist opening my brokerage account to try manually recreating the options structure of a structured note.

Theoretically, I knew the basic construction: buy an at-the-money call, sell a call with a strike 1.3 times higher to cap the gains, and add a put spread to simulate the note's 15% downside buffer.

I asked the AI to help generate the combination, and it did produce some decent-looking payoff curves. It seemed like placing the trades would replicate the bank's note structure.

But I didn't actually place the orders. Not because I was afraid, but because I quickly realized I had no idea how to judge if this combination was actually good value. Costs like bid-ask spreads, market depth, margin requirements, and slippage were things I couldn't easily estimate.

It reminded me of a recently popular term: "Vibe Coding."

When engineers get tools like Cursor, they sometimes feel programming isn't that hard. Some might even whip up a basic B2B system and think, "I could build WeChat." But the reality is that between a "Hello World" and a deployed online service lies a vast chasm of invisible costs: system design, operations, fault tolerance, security, canary releases.

My situation felt similar. I thought I could whip up a structured note, but I had only grasped its structural outline. Understanding the structure ≠ replicating the system.

This process made me understand more clearly: A bank note isn't just an options portfolio; it's the productized shell of an entire financial system. It encompasses credit underwriting, hedging execution, financing arrangements, repricing mechanisms, and even the narrative presented to clients. It's not that you can't build it, but if you did, there'd be no one to backstop it, narrate it, or ensure its smooth operation.

The comparison to SaaS versus self-built systems is apt: not technically impossible, just practically unsustainable.

So I stopped my DIY replication attempt and started thinking seriously: What role did AI actually play in this process? And what judgment capabilities did I gain from the back-and-forth between AI and human discussions that I couldn't have achieved alone?

AI Didn't Give Me Answers; It Gave Me a Whiteboard to Pound On

Reflecting on the entire exploration, I noticed something interesting.

The AI never made any decisions for me. It didn't tell me if the note was worth buying or which strategy was superior. Its role was more like this:

- When I threw a confusing term sheet at it, it broke the complex structure down into digestible pieces.

- When I asked if I could replicate it, it drew an options combo chart, showing the logical feasibility.

- When I suspected the note was a scam, it laid out the payoff, costs, and alternatives, providing a comparative framework.

It didn't think for me; it helped initiate my thinking process through dialogue. This is the part I most want to convey.

We often assume "understanding finance" or "understanding AI" means possessing a complete knowledge system. But through this journey, I gradually realized that true capability lies in persistently asking good questions amidst ambiguity, uncertainty, and even self-doubt. The AI's role here isn't that of an omniscient expert descending with divine knowledge, but rather a whiteboard you can repeatedly hit, test assumptions on, and challenge. You ask, it answers; you question its answer, it revises; you add new context, it tries to reconstruct its understanding. It never gets angry, and it never dismisses your questions as foolish.

Sometimes it felt like an incredibly patient partner, using "if...then..." logic to help me deduce the next layer of possibilities, automatically adjusting its explanations based on my tone and vocabulary. But what's more interesting is that its expressions weren't perfect—sometimes vague, jumpy, or incomplete. This very imperfection created space for thought. Because of these flaws, I sought opinions from others in group chats, encountered reminders about considering the strategic evolution path, and reflected on whether my judgment framework was biased towards profit maximization. If the AI's answers had been too perfect, it might not have sparked discussion.

So, the true value of AI isn't in giving you answers, but in activating your judgment. It's like a mirror reflecting your progress in understanding the structure, revealing what you tend to believe and what questions you overlook. It can even expose your cognitive path dependencies.

Only later did I realize that what I truly gained wasn't the "correct explanation of structured notes" itself, but the ability to "continuously approach understanding itself alongside an indefatigable system."

AI Can't Teach You to Think, But It Can Think Alongside You

After the whole affair concluded, a friend asked me:

So, do you think structured notes are worth buying now?

I laughed. This question was identical to the one I initially asked the AI. Only this time, I wouldn't ask someone else for a "yes or no" conclusion.

Instead, I would ask three things back:

- What problem are you trying to solve with this product? Principal protection, hedging, stress avoidance, or just diversification?

- Do you have other ways to achieve a similar goal? Like options strategies, index products, or simply doing nothing?

- What limitations and costs of this structure can you accept? Such as capped returns, low liquidity, opaque pricing?

The AI didn't teach me these questions. They are the mental anchors I formed myself as the AI forced me to keep probing during our continuous back-and-forth.

You could view this as a small, specific learning journey about structured notes. But I prefer to see it as a journey exploring the cognitive synergy between AI and humans. I increasingly feel that:

- People don't fail to understand complex things; they just dislike passively receiving complex narratives.

- AI isn't an expert making decisions for you; it's a humble partner that doesn't push its own agenda but is willing to walk paths you might not have the patience to tread alone.

- True understanding comes from your willingness to let your questions bounce between AI and humans—to be refuted, expanded upon, and refined.

More importantly, I understood something crucial during this process: Conversing with AI isn't actually replacing human interaction; it's amplifying the human desire to learn.

If I hadn't taken the AI's initial breakdown to the group chat, I might have assumed I already understood. If my friend hadn't reminded me, I wouldn't have realized the significance of the strategy translation chain perspective. If I hadn't tried to replicate the note structure myself, I wouldn't have discovered that my understanding was only part of the truth.

It was these human-to-human dialogues that pushed me constantly back to the AI, to re-ask questions, to redefine my doubts. The AI became a medium for my discussions with others and a partner in my cognitive evolution.

In the end, I realized:

Through the Q&A, I was never really seeking a definitive conclusion. I was training myself how to judge, how to reflect, how to ask better questions.

And that, perhaps, is the most structured thing I learned from structured notes.

Comments