Have you ever noticed how AI has a distinct "AI-like" way of speaking? Here's an example: when I asked AI to translate a Chinese sentence, a human might say something like "We need a few APIs so clients can submit tasks and get task IDs to track progress." But AI translates it as "The system shall provide multiple distinct APIs that facilitate client task submission and generate corresponding task identifiers for subsequent progress monitoring purposes." It just feels off - like a leader giving a formal speech, official, bureaucratic, and distant.

This is an issue I've been grappling with for a long time. Until this problem is solved, I can't effectively use AI for translation or writing articles - it's immediately obvious that it wasn't written by me, or even by a human. Making AI's tone more like mine seems like it should be simple, but after trying it, you'll find it's particularly challenging. This article will use the example of "adjusting AI's tone to sound more like me" to introduce a powerful but complex tool called fine-tuning.

We'll first discuss how we discovered through various failed attempts that the core challenge lies in getting AI to internalize detailed and specific guidance. Then we'll cover which scenarios are suitable for fine-tuning and which aren't. Finally, we'll discuss some technical tips needed for fine-tuning.

Repeated Failures

The most intuitive approach to controlling tone is, of course, Prompt Engineering, which was my first attempt. But one major challenge is how to help AI strike the right balance. If we simply say "make your tone less formal," it often swings to the other extreme. The AI starts being overly casual and playful, which isn't what we want either. So, the challenge lies in how to clearly describe to AI exactly where we want it to land between these two extremes of formal and informal.

After trying to describe the desired tone using abstract descriptions but still failing to effectively adjust AI's tone, I tried another approach. This inspiration came from my experience with Midjourney for image generation. I wanted to express a style that was intricate in detail but not too flashy, and struggled to describe it in words for a long time. Then an expert suggested trying "Rococo style," and it immediately produced exactly what I wanted. Similarly, Hemingway's writing style is hard to describe precisely. You could use lots of words to describe Hemingway's characteristics - his short sentences, direct language, and use of understatement - but it would still be very difficult for AI or humans to write in Hemingway's style based on just these descriptions. However, because AI has seen Hemingway's works during training, if you directly ask it to write in Hemingway's style, it can imitate it quite well. This is the power of background, school of thought, or what we might call imagery.

Therefore, my second approach was to try to help AI find some abstract concepts from similar writers or schools of writing that could help it understand exactly how to handle the tone. Unfortunately, after working with AI for a while, we couldn't find any writer's or school's style that could effectively capture my style. After all, those who leave their mark in literary history are masters - using their styles to approximate someone as ordinary as me was indeed too challenging.

Although this direction failed, it brought some insights: if we want to achieve more detailed control, mere description isn't enough - AI needs more information. When there's an existing concept, this information can be condensed into a single word, but when there isn't a ready-made concept, perhaps we can give it many examples to learn from in real-time. This is the few-shot learning approach. Specifically, when giving it a translation task, I would not only provide the original English text but also attach several previously written articles, hoping it could follow these examples to produce translations that sound less AI-like.

But unfortunately, this approach also failed. After some reflection on why, I realized that trying to construct a complete style from just a few articles was probably asking too much. Especially when the articles cover different domains, where relevant terminology and word usage habits have no direct references, it ultimately falls back on AI's own knowledge base. And then it reverts to that leadership speech style.

If this is the reason, it's not actually hard to solve. Instead of randomly grabbing a few articles as examples, we could first do a retrieval on my previously written articles and then use small sections that are relevant to the text being translated as examples. This way, we can ensure that the examples AI sees are closely related to what it needs to translate, greatly improving the efficiency of providing background material to AI.

But sadly, this method failed too. Compared to native AI translation, results using this method either showed no significant difference or couldn't achieve relatively fine-grained control. Beyond this, I also tried tools provided by other products, including Claude's style feature and various different AIs (side note: Gemini AI sounds the least AI-like), but from an abstract perspective, they didn't go beyond the approaches described above, and the results weren't ideal.

Fine-tuning: AI's Weapon for Internalizing Precise Corrections

Although these methods failed, they were still enlightening: why is this problem difficult? Mainly because it's not a clear requirement that can be easily described in language. AI has read countless books and has certainly encountered this kind of plain, friendly language style. In some of our previous attempts, we could see that it is capable of speaking in my style - the core problem is how we express to AI exactly what this style is.

Why is this expression difficult? There are two main reasons. First, it's very precise. For example, looking at the translations above by AI and me, they differ by just a few words, but the tone and style are vastly different. Second, perhaps because of this precision, if AI wants to internalize these corrections, it needs many examples, preferably covering various topics and scenarios. In other words, our core problem is how to get AI to internalize these scattered, trivial, yet precise corrections and guidance. Our traditional weapon is prompting, but it seems inadequate for such needs.

What is Fine-tuning

This is where fine-tuning naturally emerges as a solution. Fine-tuning isn't a new concept. As we discussed in a previous article, before foundation models emerged, fine-tuning was actually the primary method of using models. Modern AI (LLM) is based on zero-shot learning or few-shot learning, using examples provided in the input text to dynamically learn and understand user intent before producing output. Throughout this process, the model itself doesn't change.

Fine-tuning is exactly the opposite - it needs to change the model's content itself to achieve changes in the model's behavior. Specifically, it needs to show the model lots of training data, where each piece of training data has an input and an expected output (ground truth). The fine-tuning algorithm will change the model's content (weights) to make it produce outputs as similar as possible to the expected ones for given inputs. Through repeatedly adjusting these weights, the model can internalize the information we're conveying through the training data.

A simple example is that we can fine-tune a model to determine whether a customer review is positive or negative. Here, the training data input would be the customer review itself, and the output would be the positive or negative judgment. The model fine-tuning process is continuously adjusting model parameters so that when it sees each input customer review, it can give the correct judgment.

Of course, judging customer reviews is a toy example - modern AI can do this well without fine-tuning. But for more complex needs, like detecting passive-aggressive comments, fine-tuning becomes a powerful weapon. Fine-tuning allows us to provide the model with many examples, letting it carefully consider and understand how to make judgments under different conditions and scenarios, and then internalize these scattered, precise corrections.

However, this modification to the model itself is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can effectively help the model accept lots of guidance; on the other hand, because the training model is so large, it's also a very heavyweight process. On one hand, we need to prepare quite a lot of training data, like hundreds or thousands of input-output paired samples; on the other hand, we need to load a huge model into GPU memory and use massive GPU computing power to make tiny changes to the model's weights.

Therefore, fine-tuning often requires spending lots of time on data collection and cleaning, code writing and debugging, and final quantization and packaging. Meanwhile, the whole process is full of risks and uncertainties. Especially for large language models, fine-tuning might cause huge changes in model behavior. For example, it might completely forget previously learned skills or knowledge (catastrophic forgetting); or the entire model might collapse, becoming a useless model that only babbles nonsense; or the model might become overly talkative, continuing to output seemingly relevant but actually nonsensical content after completing the task.

Additionally, fine-tuning has high hardware requirements - if using a consumer gaming GPU for fine-tuning, memory typically maxes out at around 1B (one billion) parameters. If you want to do practically valuable fine-tuning, you need at least four 4090s, and much larger GPU clusters are quite common. Therefore, it's a very heavyweight operation. This is why I kept it in my backlog and tried other methods first.

Suitable and Unsuitable Scenarios

From the purpose of "internalizing precise corrections," fine-tuning naturally has scenarios where it excels and others where it's not suitable. Changing AI's output style is a common scenario for using fine-tuning. This includes things like tone, or its output format (like JSON), or tool usage. For example, if I have 50 available tools and want AI to make choices among them, using appropriate tools in appropriate situations.

In these scenarios, fine-tuning the AI model has two benefits. The first benefit is that it can achieve more precise control than other methods, even complex PUA (Prompt Utilization Architecture, the next generation of prompt engineering). The second benefit is that it can greatly reduce prompt length. For example, even if we can use specific examples to change AI's tone, or use prompts to explain to AI the specific functions and usage of those 50 tools, we need to process and understand these prompts from scratch each time before starting output. This has significant disadvantages in both cost and response time. But if we use fine-tuning to internalize these prompt requirements into the model, we can use very simple prompts to get the same output from AI. In such cases, both user response and inference cost are greatly improved. Therefore, these scenarios are more suitable for fine-tuning.

There's a widespread misconception about fine-tuning that it can be used to inject new knowledge or skills. This is incorrect. Fine-tuning is more like inspiring and activating AI's existing abilities - it can't give AI a new ability. Or things like stronger reasoning and more knowledge. If you're interested, you can try fine-tuning a knowledge base into AI and compare it with RAG to see if it can effectively utilize this knowledge. I've done such experiments, and the conclusion is it can't. But I'm also curious about others' experimental conclusions.

Key Technical Decisions in Fine-tuning

But as described above, after trying various methods without success, and with fine-tuning seeming like an appropriate solution, plus having Agentic AI as a powerful tool recently, I explored how to use Agentic AI to help me complete this fine-tuning task.

Below, I'll first introduce several key decisions I made in the process of using fine-tuning to solve the AI tone problem. As we mentioned in our previous article about career development, these technical decisions are much more important than how fast you can code, how careful you are, or how much time you invest during actual operation. Because once we make a wrong decision, even if we code twice or three times faster, if the path is wrong, we'll have to start over completely. This wasted time can't be made up for by coding faster. Therefore, we'll first spend some effort to clarify some basic concepts and technical decisions, then introduce more detailed operational techniques.

We made three important decisions here:

Parameter Efficient Fine Tuning

We used a method called parameter efficient fine tuning, specifically LoRA. LoRA's basic idea is that instead of changing the entire model's billions of parameters, it uses a special low rank decomposition to greatly reduce the number of parameters to be trained. Without getting into mathematical details, one intuitive way to understand this is that it's similar to inserting some wedges at the most critical points in the model, achieving leverage through only changing these wedges' weights to significantly change the model's overall behavior.

This reduces the scale of the model training mathematical problem to a hundredth of what it was before, allowing us to effectively fine-tune relatively large models like 3B, 7B models even on consumer-grade gaming GPUs. Of course, this is still an engineering tradeoff - its effect is often not as good as complete fine-tuning, but when we don't have the conditions to purchase or rent another large GPU cluster, this is an effective compromise solution.

Reverse Data Synthesis

The second key decision is where the training data comes from. To solve the translation tone problem, the perfect method would be to provide many application texts and have humans like me translate them into Chinese, thus creating paired training data to guide training. But fine-tuning typically needs at least hundreds or thousands of training data points, and having me manually translate hundreds or thousands of passages would be too time-consuming. In enterprises, the common method is to hire people for annotation, but in our scenario, aside from the money issue, from writing annotation guidelines, determining examples, to communicating with annotators, acceptance, iteration, etc., this itself is a time sink. Large enterprises can assign a person or even an entire team to do this and still ensure profitability. But for us individuals, it's completely unrealistic.

Therefore, regarding data, I directly used LLM to generate data. Specifically, I took advantage of current LLMs' natural translation tone, first extracting all my Chinese blog posts as input, then having AI translate each natural paragraph into English. This way we have data pairs where the input is Chinese and the output is English. Then we reverse it, making the translated English the input data and my written Chinese text the expected output, thus conveniently constructing large amounts of training data.

For example, if my blog mentions "提供几个不同的API,让客户端可以提交一个新任务,然后返回一个任务的ID", this sentence translates to English as "Offered several different APIs. This would allow the client to submit a new task and receive a task ID in return". Then we take this English passage as input and tell the fine-tuning program to adjust this model's parameters so that its output matches my written Chinese passage as closely as possible. Through this method, we obtained lots of training data.

Using Commercial APIs for Opportunity Sizing

My third technical decision was Opportunity Sizing. As we mentioned earlier, fine-tuning itself is a very heavyweight operation requiring lots of effort, with a high risk of failure. Therefore, before we commit to investing the most effort, we need to test the waters first to see if this method has any hope of success. Considering the high cost of code writing and cluster rental, I directly used OpenAI's fine-tuning API for Opportunity Sizing.

Specifically, I selected a small portion of the training data, went to OpenAI's website, and tried GPT-4o's fine-tuning feature first. Fifty training data points cost three dollars, but from the returned model, it had to some extent achieved control over tone, with less AI flavor than native GPT-4o. Therefore, I further increased investment, using more training data for a larger-scale verification. The results were quite encouraging - under some examples and reasoning parameter settings, it could achieve quite good results, sometimes I even thought the sentence was really written by me. But on other examples, its effect was still not satisfactory, sometimes even experiencing collapse. And the whole process was quite expensive - even fine-tuning on a subset of the training data cost me a hundred dollars.

Therefore, through using OpenAI's API, I temporarily avoided the tedium of code debugging and infrastructure rental, verifying through a definitely correct implementation that this direction has promise. But at the same time, because it was really too expensive, it also made me determined not to continue using GPT-4o for fine-tuning, but rather to use open source models to reduce costs while achieving greater flexibility. After all, OpenAI's API hasn't exposed all fine-tuning related parameter settings, and it's possible that in our needs, to improve the fine-tuning effect, we need to adjust those unexposed parameters.

Core: Lowering Barriers

These three decisions have a clear thread: lowering barriers.

The whole technical decision process was like this: we first used LoRA to solve the problem of computing power barriers being too high, used AI semi-synthetic data to solve the problem of data barriers being too high, used OpenAI's API to solve the problem of implementation correctness barriers being too high, confirming the feasibility of this approach at a cost of 100 dollars, and made the decision: we need to invest more effort in fine-tuning on the source data. Below we'll specifically introduce what techniques we used in the actual execution process to make this very complex project become reality within a few hours.

Fine-tuning Implementation Details

The process of implementing fine-tuning is relatively intuitive with the help of Agentic AI - basically just describe to Cursor what you want to do. But there are also some pitfalls. Here are several lessons learned.

Hardware Deployment

There are generally two methods for deploying fine-tuning: one is to use services like OpenAI's fine-tuning API. The reason OpenAI's API is expensive is mainly because GPT-4o is a particularly large model. But if we want to directly fine-tune open source models, whether AWS or AnyScale, there are many similar APIs available, and they're much cheaper than fine-tuning GPT. Moreover, since the models are open source, we can also do many customizations.

The second method is to directly rent a GPU machine or cluster - this is exactly the same as renting a virtual machine online, the only difference being that this machine has GPUs, so we can completely customize it, doing whatever we want.

In my scenario, because I wanted to explore the pros and cons of fine-tuning in multiple ways, I used the second approach. Specifically, I rented an NVIDIA GH200 on Lambda Labs. They recently had a promotion for just 1.8 dollars per hour, which is very cost-effective for a machine with 64-core CPU + 520G memory + 96G GPU memory H100. Overall the experience was good, but the only catch is that its CPU is really weak compared to traditional server CPUs, so some additional optimization is needed, like using multiple cores for data processing to ensure CPU isn't the bottleneck and to get GPU utilization up.

Document Management

Fine-tuning is a very complex project - for example, the core program of my final version of fine-tuning has eight or nine hundred lines. Therefore, if we still mindlessly use Cursor to write programs like before, we often fall into a situation of going in circles. For example, it corrected an error earlier under our guidance and correction, but after multiple rounds of dialogue, possibly because the previous correction fell outside the context window of the latest round of dialogue, it lost this background knowledge and changed it back in the new round of changes. This is a typical failure pattern when using Cursor for large-scale engineering implementation.

Solving this problem requires the Document Management we mentioned before - that is, after it fixes an error, we can use prompts to have it write newly learned experiences to .cursorrules, so this requirement becomes part of the prompt sent to AI each time, and it won't make this mistake again in the future. But with the release of the latest version 0.44 of Cursor, I found it becoming increasingly insensitive to this instruction. So if needed, it's still more reliable to manually explicitly have it summarize experiences. Additionally, having it maintain an overall plan and current progress in .cursorrules is also an effective way to prevent it from starting to busy itself with another unrelated thing halfway through.

Overall, in the process of using Agentic AI for programming, our role is more like a development manager, with main responsibilities being evaluating development effects, guiding development direction, and synchronizing development progress, while inspiring AI to take appropriate notes so that it can also grow. An interesting point is that in this article introducing fine-tuning, I haven't mentioned at all what libraries or frameworks we need to use. This is because now these are all handled by Agentic AI - we don't need to pay attention to them. Our energy should be spent on making decisions like "whether to use fine-tuning" and the various key decisions mentioned above.

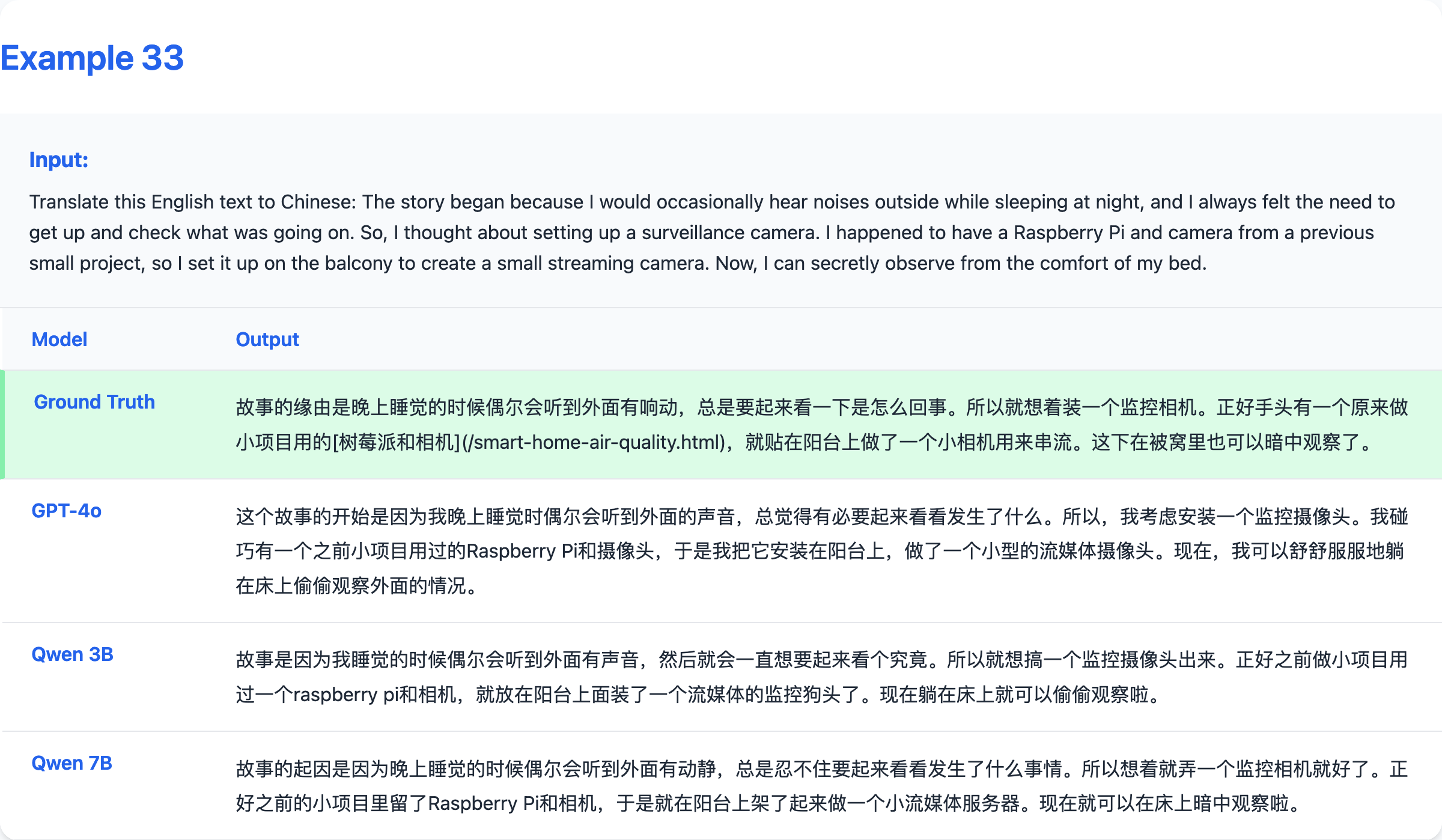

More Auxiliary Tasks

After using Agentic AI to do the core fine-tuning task, we can also have it do more Unit Tests, as well as quantization visualization and inference work. For example, combining with the data engine, we can have it first merge the training-generated Hugging Face format model with the LoRA model, then use llama.cpp for quantization and inference on Mac. Additionally, we can have it generate comparisons with commercial models - for example, this webpage demonstrates the comparison between GPT-4o and my fine-tuned Qwen 2.5 3B and 7B models.

Above is a specific example - we can see that the fine-tuned model's grasp of tone is quite accurate, often very close to the reference answer.

Summary

Overall, we solved the difficult problem of precisely controlling AI's tone through fine-tuning. Throughout the process, there are several points to remind everyone about.

-

Fine-tuning is a technology with great flexibility, but also significant limitations and risks. Before using fine-tuning, we generally try many lighter-weight attempts first, then take the fine-tuning route. And even before actually fine-tuning, we'll first use mature APIs to do some opportunity sizing to avoid wasting time and keep risks under control.

-

But the good news is that now even for ordinary consumers, fine-tuning is an accessible weapon. Algorithmically, we can use memory-saving algorithms like LoRA. For data, we can use LLM to generate data. And for hardware, we can rent ready-made APIs or hardware from cloud service providers.

-

Even with these techniques, fine-tuning is still quite challenging for Agentic AI. Therefore, in this process, we need to be especially careful to have AI maintain a document from start to finish, summarizing our goal plan and its learned experiences on it. This can greatly improve AI's work efficiency and avoid falling into the trap of repeatedly making the same mistake.

Comments