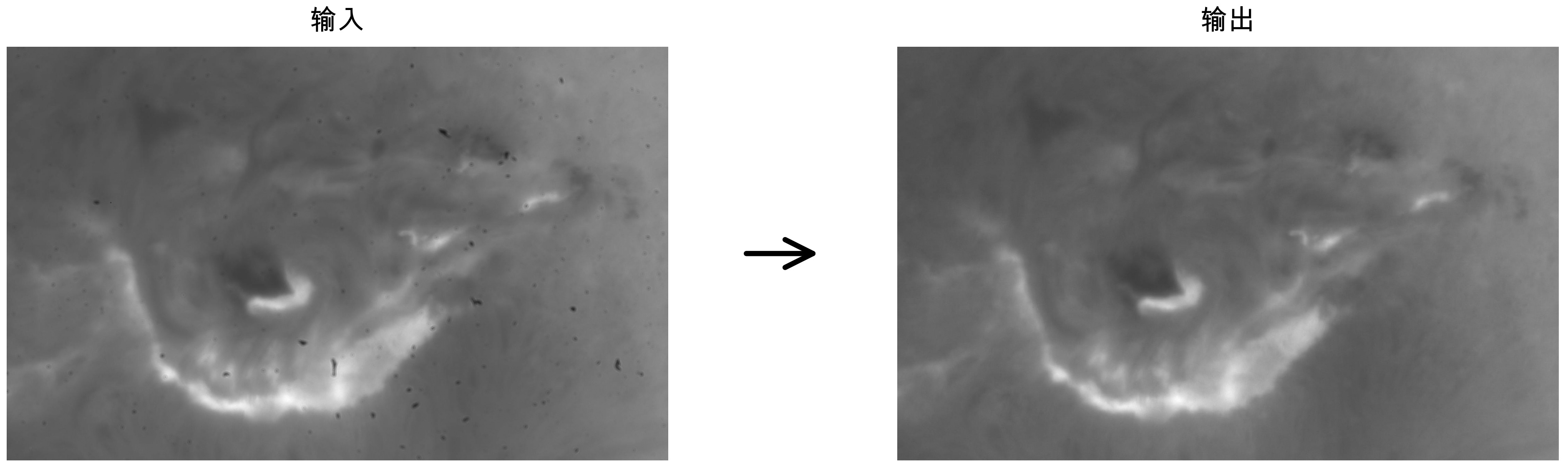

It all started with a video file of the solar surface shared by Mr. De Lai from the Shenzhen Astronomical Observatory. Due to various environmental factors, their CMOS sensor had accumulated significant dust. When observing the sun with a high f/40 focal ratio telescope, these dust specks became painfully obvious in the footage. He was looking for a way to remove this dust from the video—something that could take a raw frame and produce a clean output, as shown below.

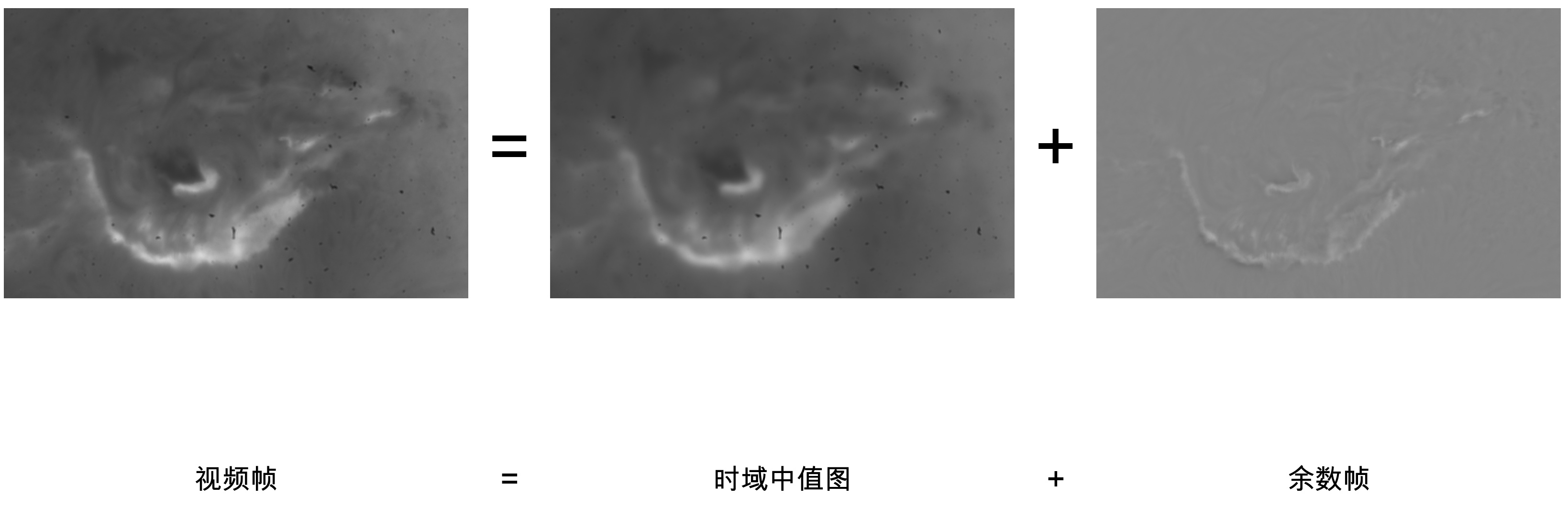

I initially attempted several traditional approaches, but quickly realized how tricky the problem was. The dust wasn't close enough to the CMOS to be easily removed by standard flat-fielding, yet it wasn't far enough away to be just a blur. Because of the high focal ratio, the specks were sharp but not pitch black, making simple thresholding ineffective. I tried the classic KLL self-flat-fielding algorithm (Kuhn, Lin, and Loranz, 1991), but the poor seeing conditions on that day rendered it ineffective. I also tried generating a temporal median map from the entire video. While this could isolate static features (the dust), it also inadvertently captured low-frequency solar structures, as seen below. This calibration method was clearly flawed.

Just as I was about to give up, I wondered if modern generative AI models, like Google's Nano Banana Pro, could help. Instead of writing complex rules, we could simply provide a frame and tell the AI: This is a solar image with dust; please output a clean version. This end-to-end approach is fundamentally different from traditional computer vision. Traditional methods involve multi-step pipelines: median filtering, brightness rules for spot detection, morphological checks for dust identification, etc. AI, however, maps input directly to output in a single step. We only need to describe the desired result in natural language.

I wrote a simple prompt to test this theory, and the visual results were stunning—as seen in the opening comparison. The after image was generated entirely by Nano Banana Pro.

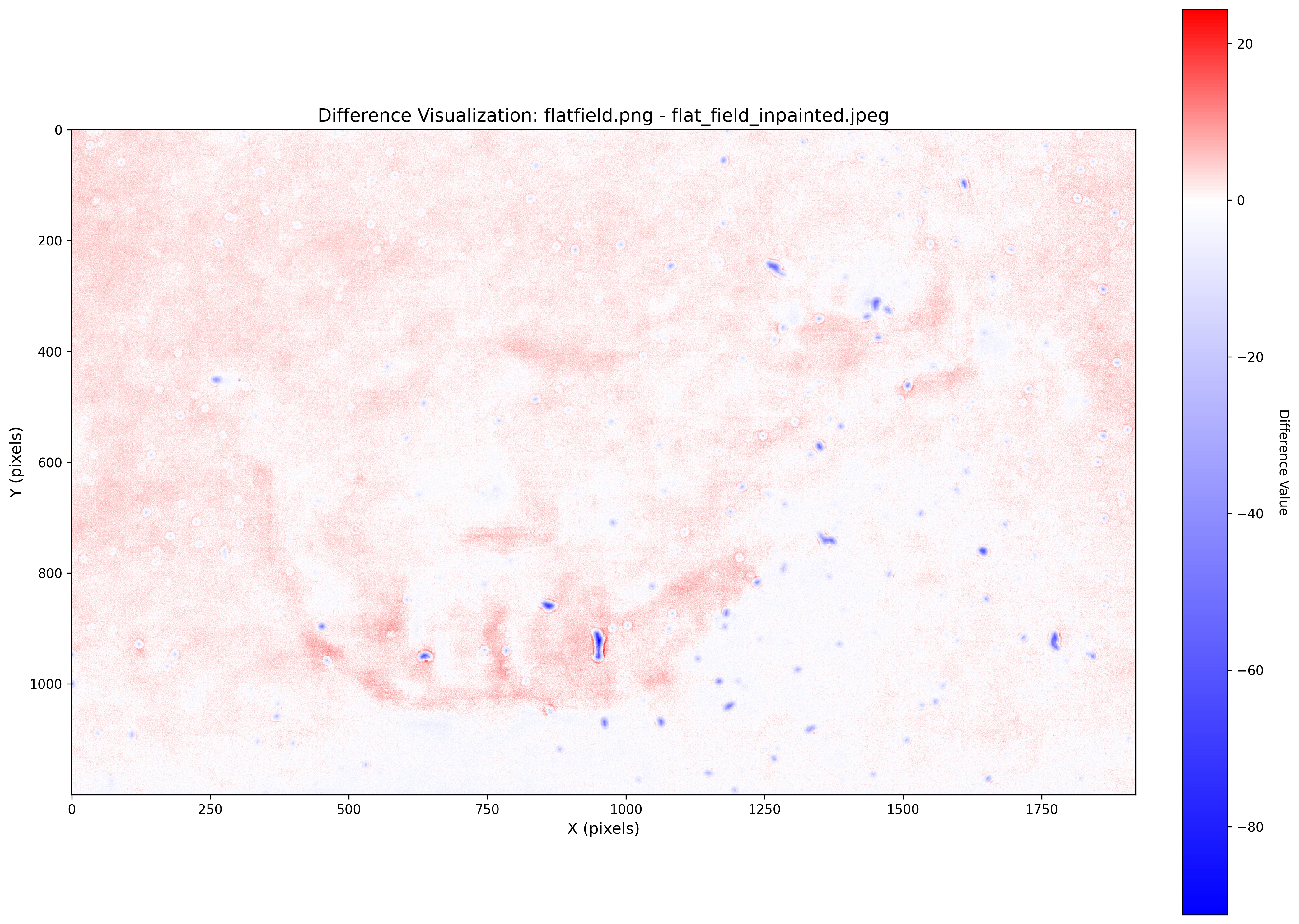

However, while the results looked great to the naked eye, quantitative analysis revealed a major issue. While the AI-generated image appeared close to the original, mathematical comparisons showed that the model had introduced numerous subtle changes. Local brightness was altered, and nonexistent textures were added. These artifacts might be subtle in raw data, but they become glaring issues after heavy stretching or deconvolution. More importantly, such hallucinations could be misleading for scientific research, potentially leading a researcher to mistake an AI artifact for a groundbreaking solar feature.

This realization brought us back to square one. Traditional algorithms are safe because they follow strict physical rules, but they are often blind because they can't distinguish between dust and solar features. Conversely, end-to-end AI is sharp at recognizing patterns but unreliable because it likes to improvise textures. Our core challenge became: can we combine the two? We wanted the AI’s eyes (recognition) but the traditional algorithm’s hands (deterministic pixel manipulation).

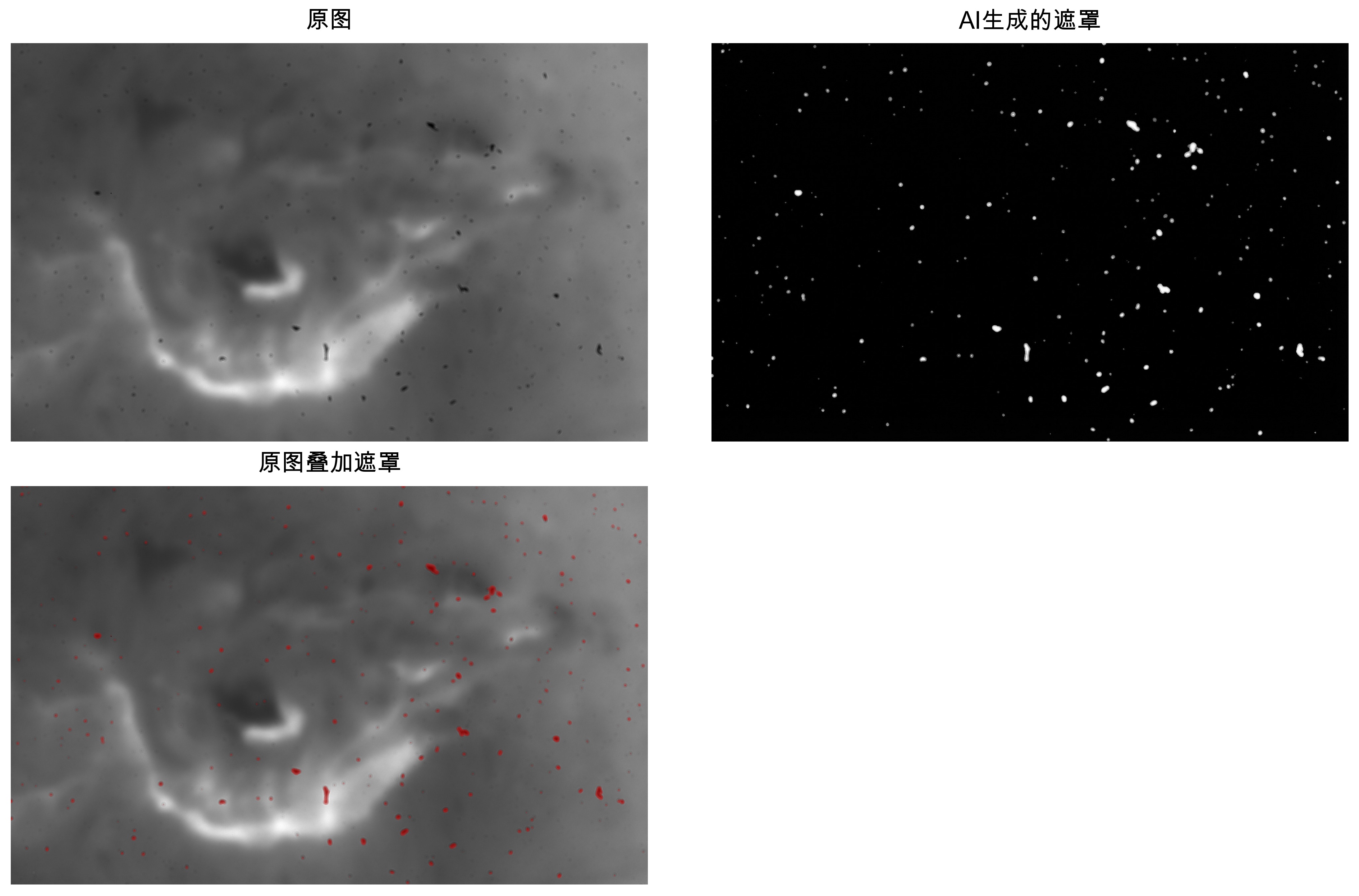

Breaking down the end-to-end AI process, it actually performs two distinct tasks: localization (finding where the dust is) and correction (deciding how to change those pixels). By coupling these tasks, we lose control. A more effective strategy is to decouple them. First, we let the AI handle only the localization. If it can do that well, we can then use deterministic math to ensure the correction only happens where the AI pointed. So, I modified the prompt: instead of a clean image, I asked the AI to generate a binary mask (1 for dust, 0 for clean solar surface).

The result was extraordinary. The AI perfectly identified every dust speck while completely ignoring actual solar structures. Even with half an hour in Photoshop, I doubt I could have produced a more accurate mask manually.

From a research perspective, this mask alone is invaluable. It means we can simply exclude these masked pixels from our analysis, ensuring they don't skew the statistical profile of the rest of the image. For many scientific applications, the problem is effectively solved right here.

But there are two deeper implications to this approach.

First, mapping a dusty image to a mask is an asymmetric task. It's incredibly easy for a human to verify if a mask is correct—just overlay it. But creating that mask manually is tedious and time-consuming. AI turns this asymmetric task into a symmetric one by automating the hardest part (creation), leaving the easy part (verification) to the human. This represents a massive efficiency boost—often 10x or 20x—without changing the fundamental scientific workflow.

Second, this approach democratizes high-end image processing. Since the 2010s, deep learning has become popular in astronomy for tasks like meteor detection or crater mapping. However, these methods usually require massive datasets, significant compute, and a team of PhDs and engineers. For our dust problem, a traditional deep learning project would require labeling thousands of images and training a custom model—a barrier far too high for most researchers. But with the AI mask approach, we just described what we wanted in plain language and called an API for a few cents. This shift—from building models to describing needs—is revolutionary.

However, the story doesn't end with masks. While masks are great for science, for aesthetic astrophotography, we often want to fill in the missing data through inpainting. To do this safely, we used a bit of math to generate a synthetic flat field, as shown below. Specifically, we took the AI's hallucinated clean image and divided it by the original dusty image to get a ratio. We then forced every pixel outside the AI-generated mask to exactly 1.0.

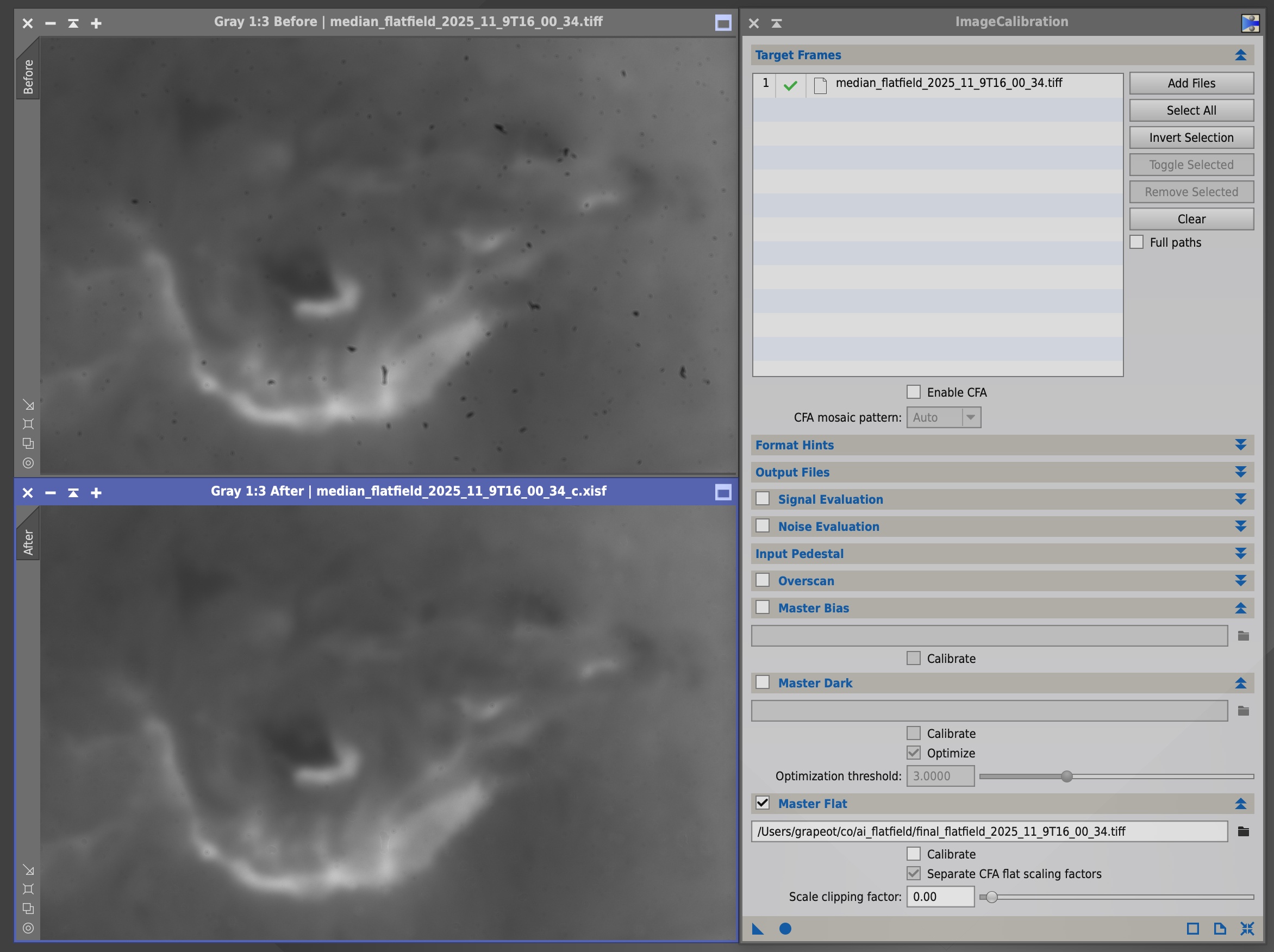

Because this synthetic flat is exactly 1.0 everywhere except for the identified dust specks, it ensures that no part of the original solar texture is modified during calibration. The actual correction is then performed not by the AI, but by deterministic software like PixInsight using standard flat-fielding math. The final result is shown below.

This synthetic flat field is our final output. By providing this to PixInsight, we can batch-process entire videos to remove dust while maintaining scientific integrity. This solves the hallucination problem of end-to-end AI: by mathematically constraining the AI's output to only the masked regions, we eliminate any chance for the model to improvise on the actual solar features.

In this workflow, the AI's role evolves from an artist with a free-hand brush to a constrained engineer. We leverage its visual intelligence for the dirty work of finding dust—a task too tedious for humans and too complex for simple rules—but we leave the final pixel values to our trusted, deterministic tools. I believe this model—AI as a generator of intermediate constraints for traditional algorithms—is a promising direction for scientific image processing. It preserves the interpretability and auditability required by science while harnessing the incredible power of generative AI.

In the future, the most valuable skills in astrophotography—and perhaps astronomy as a whole—may lie in designing these workflows, constraining uncertainty, and mastering the art of communicating with AI.

PS: To demonstrate the reproducibility of this approach, I have open-sourced the project on GitHub: https://github.com/grapeot/ai_flatfield

Comments